Georgia book banners work in secret, but anticensorship movements are growing

Just in time for Banned Book Week, running from October 5 through October 11, PEN America announced on Wednesday that an unprecedented 22,810 books have been banned in the United States since 2021. Book censorship may seem less pervasive in Georgia than it is in states like Florida, Iowa and Texas, which dominate PEN’s banned books list. But Georgia’s public schools and libraries, along with the state Legislature, are no strangers to literary censorship, and the state’s pro-censorship activists use the same playbook as their more prolific counterparts.

“While the public reporting of school book bans in Georgia might be less than a state like Florida or Texas, similar pressures are visible in terms of legislation and advocacy groups,” said Tasslyn Magnusson, senior advisor to PEN America’s Freedom to Read program.

According to Magnusson, book banners rely on two key pressures: state legislation and the influence of usually small “parental rights” groups that advocate for censorship. Those groups use specific strategies to encourage “soft” or “quiet” censorship, where books are removed from shelves without being publicly challenged.

“There are many ways to censor materials in schools beyond conventional book bans,” Magnusson says. “And Georgia, like many states, is subject to this censorship.”

Public school subterfuge

Georgia has been at the center of book ban controversy since 2022, when Forsyth County Schools banned eight books dealing with race, gender and sexual orientation. After nearly a dozen Civil Rights complaints were filed with the U.S. Department of Education, the county agreed to return the books to shelves. However, in January 2025, denouncing book bans as a “hoax,” the Trump administration released the district from the terms of its agreement. By May, a total of 23 books were either restricted or under review in Forsyth County — though none were officially “banned.”

More on ArtsATL: Department of Education has declared all book bans a “hoax.”

Similarly, Marietta City Schools drew significant criticism in 2023 when it officially banned 25 titles. Despite assurances to parents, the district has continued instituting soft bans within its schools. Marietta in the Middle, a nonprofit coalition monitoring the issue, has called attention to the district’s removal of numerous books from its curriculum and the “loss” of several commonly banned books from its media centers.

Calling book bans by another name — like “removal” or “restriction” — is popular among banners because it avoids drawing the negative attention that comes with censorship. Cobb County Schools Superintendent Chris Ragsdale, for example, consistently likens the removal of books chosen by the district’s librarians to the motion picture rating system. With 36 official bans, Cobb County schools are the most censored in Georgia.

More on ArtsATL: Book bans double down in Cobb County.

Another common tactic among pro-censorship activists is flooding school and library boards with dozens of book challenges at a time. Challengers use the number of books challenged to accuse teachers and librarians of “grooming” or “indoctrinating” students, frightening parents and intimidating institutions into removing books they find unpalatable.

“It only takes a couple of people in a community to create thousands of challenges that overwhelm a library system or a book and make it seem like the problem is more [than it is],” says Laurel Snyder, who helps coordinate the Georgia chapter of Authors Against Book Bans (AABB). “It’s much, much easier to accuse somebody of something than it is to prove that that thing is not true.”

In the Columbia County School District, for example, a solitary non-parent successfully instigated multiple book bans in May, seemingly outside of the district’s procedural rules. A subsequent open records request revealed that the district’s media policy had been quietly changed to “make it far easier to remove or restrict library books while limiting public oversight,” according to the Freedom to Read Coalition of Columbia County (FTRCCC).

Procedural changes like these are common on school boards, facilitating unpopular policies that allow them to quietly remove potentially controversial books. SB 248, introduced this year in the Georgia state Senate, may make this even easier. The law would establish the Georgia Council on Library Materials Standards, a 10-member council appointed by state leaders, which would create a grading system to determine standards for materials held in the state’s school libraries, allowing materials deemed “obscene” to be banned.

Snyder, who writes children’s books and is regularly invited to visit schools, said there’s a palpable difference between schools that value books and schools that don’t. “You start to see schools where the library has disappeared, and you start to see what it’s done. Literally, you’ll walk through a hall and see a padlocked library.” She explains that she’s often brought in by PTA members who “feel this lack of interest in literature and literacy.”

“There’s something about knowing the library is there,” she said. “Walking past it. Hearing people reading books to each other, just being exposed to it, even for the kids who don’t love to read. The loud story times, the literacy games, the puzzles … You’re creating a culture, and it will benefit different people differently, but the general benefits of that culture are undeniable.”

Libraries under attack

Despite growing demand for library services in Georgia, lawmakers in the state Legislature have circulated a bill, SB 74, that would allow librarians to be prosecuted for distributing books later deemed obscene. “This bill could make it impossible for us to do our jobs,” one Georgia librarian told the Lanier County News. “We’d be expected to monitor every item and every user, and we simply can’t do that — especially with kids checking things out on their own using self-service kiosks.” This is particularly troubling given the bill’s lack of clear guidance for which materials should be considered inappropriate. The bill passed the state Senate in a party-line vote in March, but the state House never voted on it. Its sponsor, Republican Max Burns, has indicated that he will work to pass the bill in 2026.

Librarian criminalization bills like SB 74 are on the rise. Experts believe they aim to cultivate mistrust and paranoia around libraries and their staff and increase soft censorship by intimidating institutions into removing material that may be perceived as inappropriate before complaints happen. For example, when removing potentially controversial books from their classrooms, teachers have cited Georgia’s 2022 “divisive concepts” law, which led to the firing of at least one teacher, Katie Rinderle.

More on ArtsATL: Cobb County book bans are leaving teachers worried.

Librarians are often the first people in the line of fire when complaints arise, with or without prosecution laws. According to Snyder, libraries are “an easier place for people who would like to see books banned and censored because children are such a flashpoint for people. They’re strategic about using children’s book spaces to create wedge issues in the larger community.” Snyder says that as a writer of children’s books, she’s encountered bans for a long time. “It’s just now coming into the adult literary world in the same way, now that regular libraries are being pulled into it.”

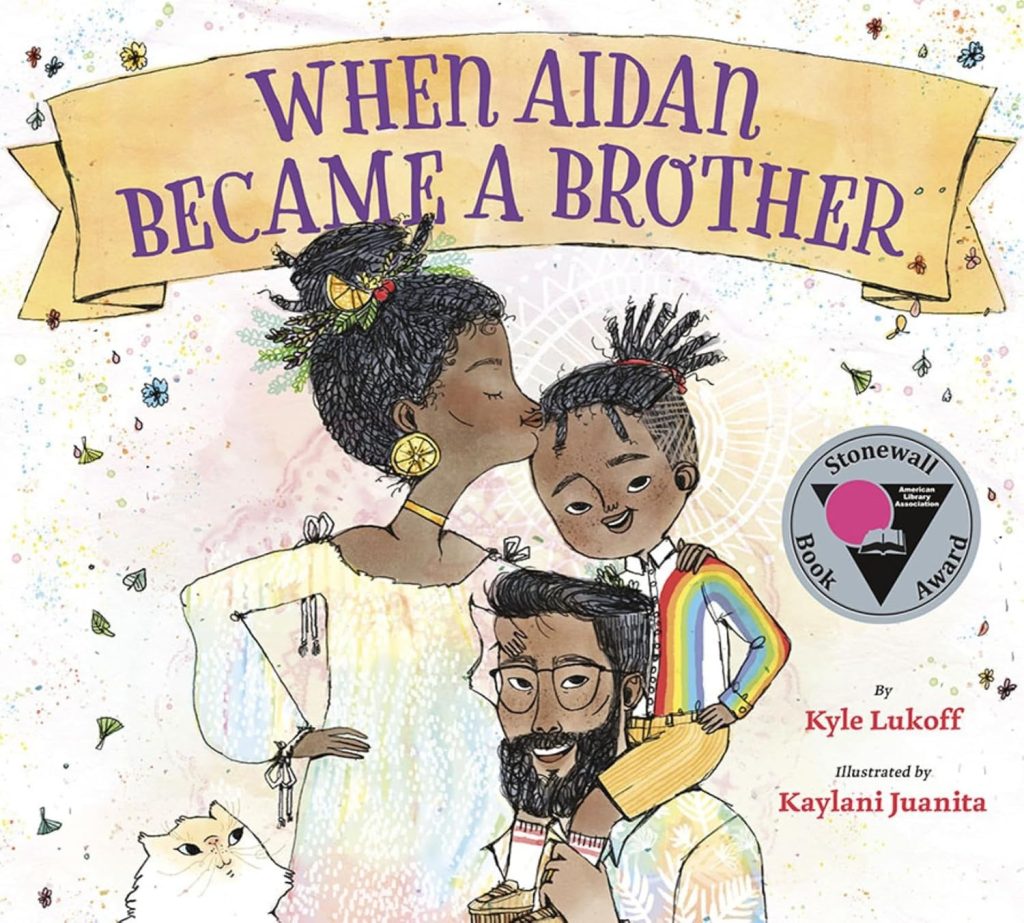

Library and school boards often fire librarians or teachers to avoid attracting ire, as in the case of Pierce County Library Manager Lavonnia Moore, who was fired in June over a library display that included a book featuring a transgender child, Kyle Lukoff’s When Aiden Became a Brother. When a photo of Moore and other staff members posing in front of the program display was posted on Facebook, it drew the attention of a local group that had previously targeted multiple libraries in the region for perceived tolerance toward LGBTQ+ people.

According to The Advocate, which reviewed library board communications released via Georgia’s Open Records Act, complaints from a small number of activists were immediately taken up by library board members who decided within hours to fire Moore. Records also showed four times as many community members writing to the board in support of Moore, but the board refused an attempt to reinstate her. Moore has since hired a lawyer, and a wrongful termination lawsuit is in the works.

“I hear from librarians all over the country that it’s hard to know what to do when they’re adding to their collections,” Snyder says. “I worry that increasingly, folks will just dodge the issue by quietly ignoring books they think might receive complaints. And we can’t fight a quiet removal like that if we never hear about it.”

The situation in Pierce County demonstrates just how destructive pro-censorship groups can be, attacking not just individual staff but entire libraries and organizations. Last year, the Pierce County Library was at the center of another controversy, this time over bathroom policies and an LGBTQ+ Pride display, resulting in the county and local school board pulling funding from the library. As a “compromise” solution, the Pierce County Library left the Okefenokee Regional Library System and joined the Three Rivers System, of which it was a part when Moore was fired.

Similarly, restructuring at the Columbia County Public Library began with a censorship debate in September 2024, when a library committee voted to move six LGBTQ+-themed books from the library’s teen section to its adult section, another common tactic of book banners. In May, local leaders announced that Columbia County libraries would leave the Greater Clarks Hill Regional Library System, establishing a new Columbia County Regional Library System in January 2026. FTRCCC has raised concerns that the change is intended to allow county officials to establish library policy without public input, and the planned changes have already led to the resignations of numerous library employees.

Growing resistance

Despite the many battle fronts in the growing war against censorship, both Snyder and Magnusson see reason for hope in 2026, as anti-censorship activists organize.

“The challenge of this feels enormous,” Snyder says. “But it’s also true that it doesn’t take that many people to affect change around school or library boards.”

Magnusson said anti-censorship movements are growing, including in Georgia, according to PEN’s The Normalization of Book Banning report. “In 70 of the 87 districts where there were school book bans, there was also resistance to those bans. We tracked that resistance in Georgia, as well, through groups like Marietta in the Middle and Freedom to Read Coalition of Columbia County.”

“We all know this is a hard moment on many political fronts,” Snyder adds, “and organizing in Georgia can feel like playing whack-a-mole.” Still, she shares Magnusson’s hope for Georgia. “The state is really diverse, and, community by community by community, this does feel like an issue where people are going to feel it … You might think you’re on one side of this issue and then realize you don’t want to lose your library.”

She takes encouragement from the sheer amount of resources available to organizations like AABB, which are just picking up steam. “We have a lot of superstars who’ve done really [big things],” she said. “Kim Jones and Angie Thomas and Nic Stone have been out there. Becky Albertalli’s done all sorts of work in the community around LGBTQ+ stuff.” She adds that the community hasn’t sufficiently leveraged the “powerhouse” writers in Georgia but expects that those connections will grow with the movement.

Ultimately, Snyder says, this is actually a solvable problem in a political moment where problems often feel insurmountable. “I believe that most parents know how hard our teachers and librarians work for our kids, that they want their kids to have access to books that represent the diverse community in this state and that if we can engage more community members, we’ll see the tide turn.”

::

Rachel Wright has a Ph.D. from Georgia State University and an MA from the University College Dublin, both in creative writing. Her work has appeared in The Stinging Fly and elsewhere. She is currently at work on a novel.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.