Three exhibitions offer variety that pleases and dismays

Atlanta is known for offering a varied bounty of art on view at any given time, a detail that frequently shows its prowess as an artistic capital. Often, this variety leaves me in wonder at how miraculous our artistic community is. At other times, this variety leaves me a little discombobulated. Across three recently opened exhibitions in Atlanta, variety remains one of our city’s strengths, but not all exhibitions rose to the occasion.

At Day & Night Projects, Kelly Boehmer presents her solo exhibition Rears Its Head (through May 3). Entering the exhibition, I was greeted by Belly Up (2025). A long, horizontal composition is anchored by a series of animals, all lying on their backs and apparently dead.

The black threaded outline of each animal is stitched into a transparent fabric behind which roils a sea of string. Although recognizable as threads stuffed into a transparent cushion, the use of creamy whites, pale pinks and ruddy browns cause these strings to read as fleshy viscera from some disgorged animal. It was almost too gross to look at.

The exhibition continues with many other artworks, all of which are unified by carnal, festering animalia. The truly breathtaking quality of this exhibition is that, although each artwork is made from everyday recognizable objects, Boehmer has transformed them so completely as to read as something else entirely. The transformation from familiar to putrid grotesquerie both attracts and repels; though I know it will not harm me, I can’t help but feel disgust and repulsion.

These morbid monsters are like a good dream gone awry, akin to a walk in the park disrupted by the discovery of a deer carcass. This exhibition creates demons from yarn as if to say our greatest fears are of our own devising.

Never have I seen textile art be so primeval. Never have I seen textile art that I loved more.

At Atlanta Contemporary, the museum presents Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant (through May 25). Originating at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York, this exhibition serves as a retrospective for the artist — presenting selections from different stages in his career.

The pièce-de-résistance of this exhibition (and Walker’s oeuvre it seems) is The Theatre Project (1983-4) series. In 32 photographs, Walker captures a voyage into and through a theater known colloquially as, according to the wall text, “a porno palace.”

The series is a moment-by-moment documentation of this exploration, but the photographs do little to showcase the verve of the palace and instead largely document seemingly random, off-the-cuff compositions. There are multiple photographs of empty staircases, several of which are so dark as to contain next-to-no discernible elements, and, most jolting, several which document homosexual sex acts like fondling and masturbating.

This series presents homosexuality as a clandestine affair, one meant to be practiced in shadows and surreptitiously, a sentiment that is enlightening for its historical accuracy.

During the outbreak of the HIV/AIDS crisis, the Reagan administration adopted a tactic of willful ignorance. This was devastating both for the resulting lack of medical care which caused the deaths of millions of people and for the intentional obliviousness that relegated gayness to the sidelines. Activists and artists increasingly used bold imagery and messages as an act of resistance and to bring attention to this devastating disease.

And yet, while Walker’s display of homosexuality captures all this, it still feels jarringly regressive today as much work by activists over the ensuing decades has focused on reversing the clandestinity of this affair.

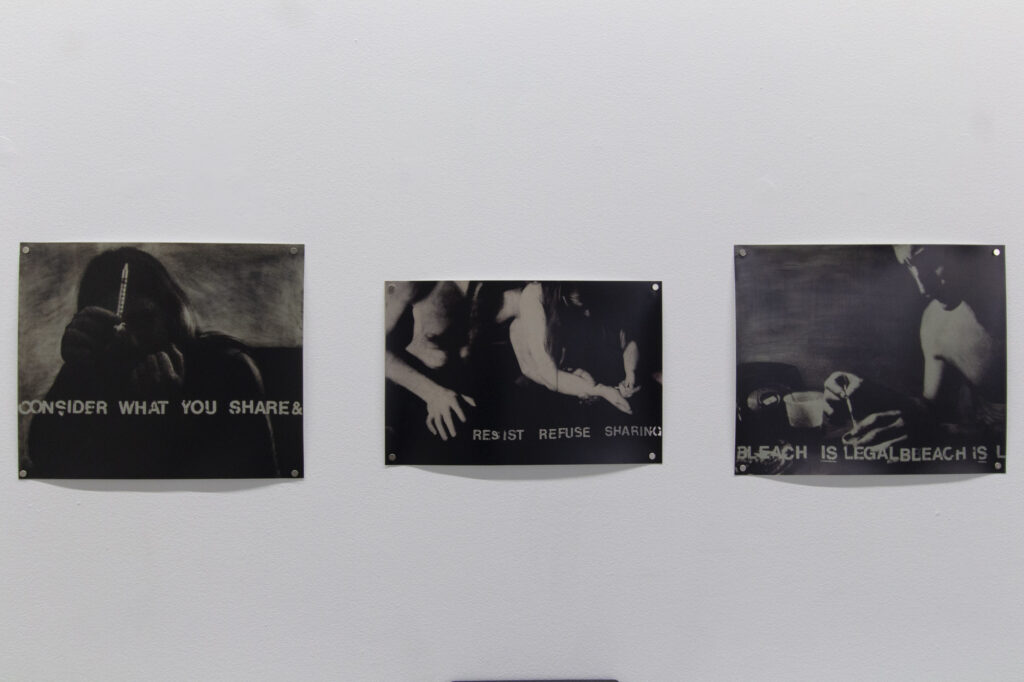

Elsewhere, the grating juxtaposition of subject matter and composition continues. Untitled Studies for Posters (1988) features three poster designs by Walker addressing the rampant HIV/AIDS crisis in the United States in the ’80s. The middle of these features the block-letter words “RESIST REFUSE SHARING” over a black-and-white photograph of two people shooting up heroin. My earlier dismay at ultra-graphic imagery was now compounded.

Shock can be used to productive effect, but its use here seems gratuitous. Rather than deepening my understanding of this theater and this epidemic, I felt it undermined them, creating an aversion. I see this as a woeful outcome when what is most needed today is greater empathy.

The Sun ATL presents a group exhibition, The Art of Math (through May 10). The concept for this exhibition is very straightforward, which turns out to be its weakness. While the exhibition concept hinges on pairing art with math, I did not find the works to express this concept coherently.

The most compelling example of integrating math with art can be found in the artworks of Ivan Moscovich. His series of harmonograph drawings elegantly pairs an exacting mathematical process with a visually stimulating medium of drawing — a testament to the exhibition’s namesake. But, elsewhere, the pairing of artwork and concept felt disjointed.

Ato Ribeiro is represented with a room full of his wooden Kente quilts. In his works, Ribeiro uses the lexicon of Ghanaian Kente weaving to vivify traditions and interweave them with contemporary cultures. This strikes a stark contrast from the mathematical processes that created Moscovich’s artworks.

Ultimately, the works in this exhibition seem to center geometric abstraction rather than the scintillating possibilities of math within art. Perhaps a reframing of this exhibition is in order because, as it stands now, the stated concept and chosen artworks feel misaligned.

::

Leia Genis is a trans artist and writer currently based in Atlanta. Her writing has been published in Hyperallergic, Frieze, Burnaway, Art Papers and Number: Inc. magazine. Genis is a graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design and is also an avid cyclist with a competition history at the national level.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.