The Beltline: How regular Atlantans created one of America’s biggest art projects

The original plans for Atlanta’s 22-mile linear park known as the Beltline contained no public art. The community had other ideas.

::

Walk any stretch of the Beltline these days, and it’s hard to imagine it without art. The urban loop is practically a 22-mile art walk. And it’s equally hard to imagine that all this art began as an afterthought but became central to the project’s development.

With more than 100 sculptures, art installations and murals, the Atlanta Beltline is the largest outdoor public art collection in the Southeast. It’s one of the largest in the country, the closest comparisons being New York City’s Highline and Madison Square Park Conservancy. But how did this multimodal walking path go from overgrown weeds and old railroad ties to one of the country’s premier public artwork projects — and in just two short decades?

“Almost all of it is from a public call, local artists,” said Amina Cooper, who in October was named the first-ever director of arts and culture at Atlanta Beltline Art (formerly Art on the Atlanta Beltline). Atlanta Beltline Art is the wing of the ongoing Beltline project responsible for commissioning and managing the public path’s numerous artworks and public events. Cooper is an Atlanta native with more than 10 years of experience in the public art world and was most recently the program director of public art at the Arts & Science Council in Charlotte, North Carolina. She took over for Miranda Kyle, who had been the Beltline’s Program Manager of Arts and Culture since 2017, curating and commissioning most of the works seen on the trail today.

More on ArtsATL: Our interview with former Art on the BeltLine director Miranda Kyle

“We issue a call to the public and convene community residents to sit on our panels and review the proposals,” said Cooper about the process of the Beltline Public Art Advisory Committee (BPAAC). “We want to make sure there’s a lot of visibility from residents and folks who are really investing in what happens in their neighborhoods.”

The vast majority of the Beltline’s iconic art — from gritty graffiti murals to large avant-garde installations — is submitted by local artists and approved by Beltline neighborhood residents. And much of it is refreshed regularly with an annual public call for proposals, meaning that the Beltline is also one of the Southeast’s biggest continual community art projects.

In its 15 years, Atlanta Beltline Art has supported and expanded a bustling, robust arts scene that includes MacArthur fellows such as Mel Chin and his fanciful, larger-than-life, boat-like sculpture Wake (installed in Historic Fourth Ward Park in 2023) and world-renowned local artists. Lonnie Holley, for example, left his mark on the Beltline in 2011 with Hands Along the Rail, a stark and industrial tribute to American railway workers. Just last year, the American Society of Landscape Architects honored Atlanta Beltline with an Award of Excellence in urban design.

“Our goal is that it’s not stagnant,” said Cooper about the ever-evolving Beltline artwork. “That it’s always reflective of what people are interested in and what they want to support and what they want in their neighborhood.” Cooper understands the importance of this process all too well; she grew up in one of these communities transformed by the Beltline, on the border between Capital View and Pittsburgh.

“The beltline runs right behind my childhood home,” Cooper said. “I remember when I was a kid, it was just the railroad tracks behind the house. By the time it was picking up speed in 2008 or 2009, I was away in college. We had moved, but we still owned that home, getting notices about the Beltline doing a survey.”

Public art was not part of Ryan Gravel’s 1999 Beltline Thesis — the document that provided much of the conceptual framework for today’s Beltline. The original designs of the corridor prioritized public transit (a topic still hotly debated today).

In 2005, even as the Beltline began to form into a patchwork of urban trails and parks amid the city’s rusted out rail lines and old industrial quarters, there was no art. Lots of random graffiti in grassy lots, yes, but no concerted project to create or support new work. What the Beltline lacked was a passionate arts catalyst.

“I started pestering Beltline officials, saying we should put signage out to let people know that’s the Beltline,” said Angel Poventud in an interview. Poventud is an artist and community activist who started following the Beltline project and attending meetings in 2004. “It dawned on me that we’re doing all these meetings but no one knows where the project is. It’s on paper, but nobody knows.” Poventud has worked as a train conductor and engineer for CSX for 19 years and at that point was still driving trains on active portions of the Beltline. “I thought there should be a signal so that people were aware that it’s all around them.”

What would become the “emerald necklace” around Atlanta was just a few dusty, weed-covered trails dead-ending into stretches of abandoned railroad tracks. However, Poventud said putting up official signage met a lot of pushback, especially over city permitting. So he reached out to WonderRoot, one of the city’s most prominent arts nonprofits at the time about creating low-budget, guerrilla art signs instead.“I said in a voicemail, ‘I have this crazy idea,’” Poventud recalled. “‘It’s probably illegal — we might get in trouble — but either way, there’s going to be a lot of fun press.’”

Although initially hesitant, WonderRoot agreed to provide $400 to pay for supplies to put up signage. “We invited people to bring paint from their houses,” said Poventud. “And we did 80 signs, a total of two boards at 40 crossings across the city, all in one night.”

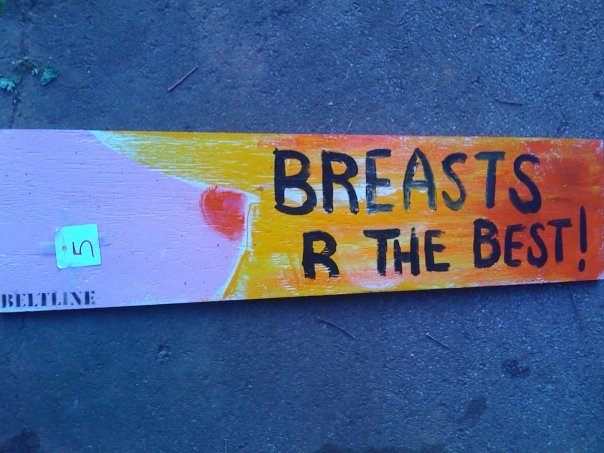

Those first “signs” — boards covered in community-created guerrilla-style art — ran the gamut from colorful, cutesy flowers and frolicking pets to more provocative declarations of “DANCE FOR UR VAGINA” and “BREASTS R THE BEST” (neither of which lasted long on the nascent trail). Poventud had been concerned about getting arrested or fined for the stunt, but Creative Loafing named it the best public art project of 2009.

“I don’t give myself credit for a lot, but this is one of those things where I’m like, ‘I started all this shit,’” laughed Poventud. “Obviously, lots of other people were being creative before I showed up, but pushing for this creative idea to put painted boards up throughout the city overnight, that definitely sparked a lot of energy and creativity that wasn’t happening in that way before we did that.”

It also caught the eye of Fred Yalouris, the Beltline’s then-director of design, who invited Poventud into his office to discuss installing art on the corridor even in its raw state. Poventud agree it could be done, and, thus, in 2009, Art on the Atlanta Beltline, now Atlanta Beltline Art, was born.

The following year, Poventud and other volunteers came back to make 240 signs up and down the Beltline. Soon, more guerrilla-style art and murals began to appear, enticing the public onto this new phenomenon taking shape in Atlanta. Those earlier projects were rawer and more impermanent, many made from found objects and materials gathered during cleanups of industrial dereliction that dotted the railways around town.

Although there wasn’t as much money in those days (“only one or two hundred dollars per project,” according to Poventud) there was an abundance of spirit and creativity that began to spread around the city. Those original projects included a massive maze made of old railroad ties created by award-winning multimedia artist Jeffrey Morrison, as well as the colorful and inclusive mural-history West End Remembers by renowned artist Malaika Favorite in 2010. That mural still stands today under the Lawton Street Bridge as the oldest piece of art on the Atlanta Beltline.

As the Beltline and its ambitions expanded, so did the scope of the projects. Longer-lasting sculptures, murals, public performances and festivals, like the popular Lantern Parade (begun in 2010), took root and continued to grow and evolve. And what started as one-off projects, such as Living Walls — an inclusive nonprofit mural generator co-founded by Monica Campana in 2010 — are still producing stunning and diverse public works today.

Atlanta Beltline Art’s public events programming last year alone included: The Weird Things, a Halloween-themed pop-up standup parade in Historic Fourth Ward Park; ATL Park Jam, an arts and hip-hop festival in Adair Park; and ATL StyleWriters Jam, a three-day graffiti crawl scattered across town at multiple locations including the Ansley and Murphy Street tunnels. Just like the artwork, these events were generated and approved by the community.

Art may not have been integral to the original Beltline plan, but it has become a vital part of its future. It’s even become ingrained in its construction with new sections, such as the nearly two-mile stretch of the Southside Trail between Glenwood and Boulevard, being designed with integrated artworks and colored walls.

“Then and today we try to re-imagine art as a way to recontextualize the environment and get the city to engage in public art,” said Cooper. “We try to make public art that is visually representative of the 45 neighborhoods of Atlanta, that we make sure that the public art is responsive and reflective of all those communities.”

Speaking of which, Cooper says the organization will be issuing the 2025 call for works soon. Like every year, she has no idea what to expect. “And that’s awesome,” she said. “It’s like a surprise and it’s always evolving.”

::

Jeff Dingler is an Atlanta-based author and entertainer. A graduate of Skidmore College with an MFA in creative writing from Hollins University, he’s written for New York Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times Tiny Love Stories, Newsweek, WIRED, Salmagundi and Flash Fiction Magazine. More information at jeffdingler.org.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.