How to Hear It: ASO performs Mozart’s ‘C Minor Mass’

Each month, ArtsATL will publish a column by Alexandra Shatalova Prior, a professional oboist who has performed nationally and internationally and is now an artist affiliate at Atlanta’s Emory University. In each column, she will highlight a few of the most interesting aspects of an upcoming work, using videos to illustrate what to listen for. This month, she takes on Mozart’s C Minor Mass,which the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Nathalie Stutzmann, will play on November 7, November 9 and November10.

::

Mozart can be a “love or hate” composer for many concert-goers, and, if you think of Wolfgang Amadeus as the fun-loving guy who wrote Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, the deep, introspective C Minor Mass is a wakeup call to another side of the composer’s personality.

On November 7, November 9 and November 10, Nathalie Stutzmann will conduct the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in an all-Mozart program, pairing his famous Symphony No. 40 with his C Minor Mass, the focus of this month’s column. Left unfinished and written during an intriguing period of Mozart’s career, the Mass is a window into the famed composer’s heart and mind at the time.

During the period in his life that he was writing the Mass (1782-1783), Mozart was living in Vienna and spending a lot of time with Baron Gottfried van Swieten, a diplomat and amateur musician who owned several manuscripts by Bach and Handel. Mozart, and others in the Baron’s company, would examine and play through the scores, which piqued Mozart’s interest in Baroque music, specifically fugal writing, of which Bach was an undisputed master. A fugue is a multivoice work that explores compositional possibilities using one theme (a “subject”) that is played or sung by all voices in succession, then developed through answers, countersubjects, inversions and modulations.

The Mass follows a specific five-part structure and is an example of Mozart trying his hand at the compositional techniques he was studying at the time. At the end of the second section — the Gloria movement — is the “cum sancto spiritu” fugue (Latin for “with the Holy Spirit”). In the following clip, listen for the way the fugue subject begins in the basses and bassoons, then moves up through the chorus and orchestral parts. You can listen for the first seven notes of the subject, or listen for the text “cum sancto spiritu” being repeated by each voice group as it is passed upward through the voices and orchestra:

The Mass is unique in Mozart’s sacred repertoire: He wrote it simply because he wanted to, not because a patron or church had commissioned it. He had recently married Constanze Weber after a dramatic courtship, and, by some accounts, he wrote the Mass as a deeply personal gesture of thanks for Constanze’s recovery from a serious illness. Mozart also claimed, in a letter to his sister Nannerl, that Constanze’s fascination with Baroque fugues — she was a trained and gifted vocalist and understood music intimately — was what led to his closer study of them and perhaps his inclusion of fugues in the writing of the Mass.

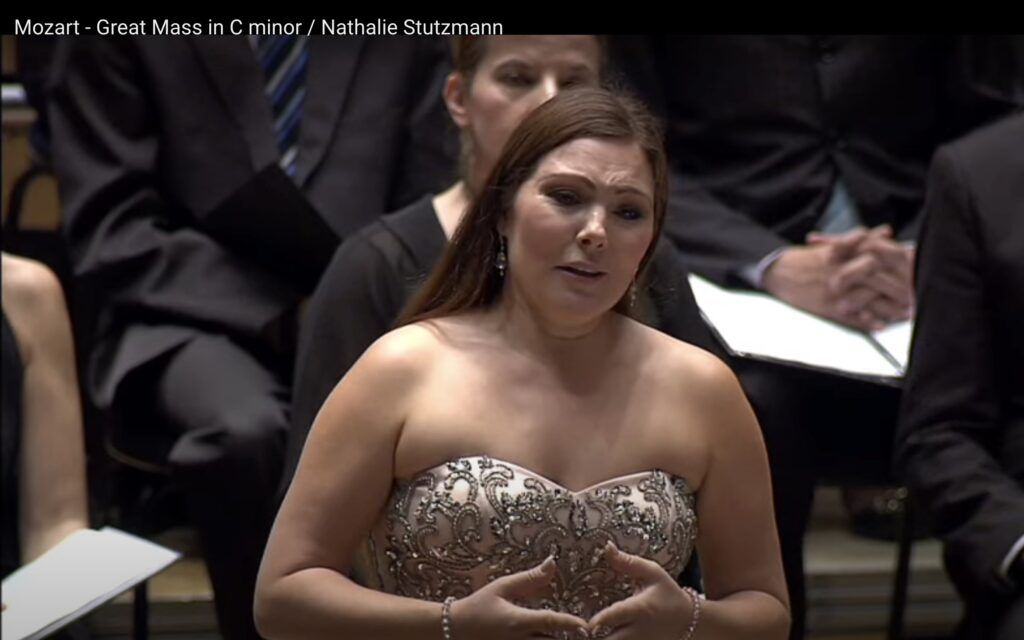

We can only imagine their conversations about music and about the Mass itself! Regardless, we know that the soprano I parts were written specifically for Constanze. You can hear Mozart’s extraordinary and tender writing for his wife in the “Christe Eleison” (Latin for “Christ have mercy”) section of the opening Kyrie movement and the aria “Et incarnatus est” (Latin for “and He was made incarnate”). Ekaterina Siurina is the soprano.

This is also the only movement of the Mass in which the flute is used, which you can see and hear in the second clip below.

The finished parts of the Mass premiered in Mozart’s hometown of Salzburg in the fall of 1783. His father (who had only at the last moment approved his marriage) and sister attended, and Constanze sang the main soprano solos. It was quite a momentous homecoming for Mozart and his new bride.

For a very dramatic rendering of the Mass, you can see the performance of Leonard Bernstein conducting it with the Bavarian Radio Symphony toward the end of his life. It was recorded in the gorgeous Stiftsbasilika in Waldsassen, near the border of Germany and the Czech Republic just a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Mozart’s famous Requiem has been the subject of much attention and discussion in music circles, but the C Minor Mass is an equally important work that continues to captivate audiences with its magnitude and unique sound.

When I listen to the Mass, it reminds me of why Mozart remains one of my favorite composers to listen to and to play: The precise counterpoint and structure is so beautifully balanced with ethereal, otherworldly, expressive moments. It appeals to both my intellectual and emotional sides.

And if the ASO performances of the C Minor Mass don’t convert Mozart nonbelievers into fans, at the very least they can be a timely reminder of humanity, unity and hope.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.