Vincent Murphy’s new memoir chronicles a life destined for theater

Growing up in Boston, Vincent Murphy never went to the theater, nor was it ever really on his radar. So it’s a bit ironic that it’s the field he’s wound up working in for multiple decades. “I really backed into it,” Murphy says now. The former Atlantan, a fixture at Theater Emory for almost 30 years, has published his new memoir, CAUGHT: A Kid with a Cup, in which he shares anecdotes about his personal and professional life. It’s available through River Twice Press and on Kindle.

More on ArtsATL: Luke Evans’ interview with Wanyu Yang, director of Theater Emory’s current show ‘Peerless.’

Murphy decided to write Caught during the pandemic, stitching together anecdotes from his life, some of which he’d already penned. He had written another book about adaptation, called Page to Stage: The Craft of Adaptation, in 2013 and some travel pieces, but he knew a memoir was a different kind of undertaking.

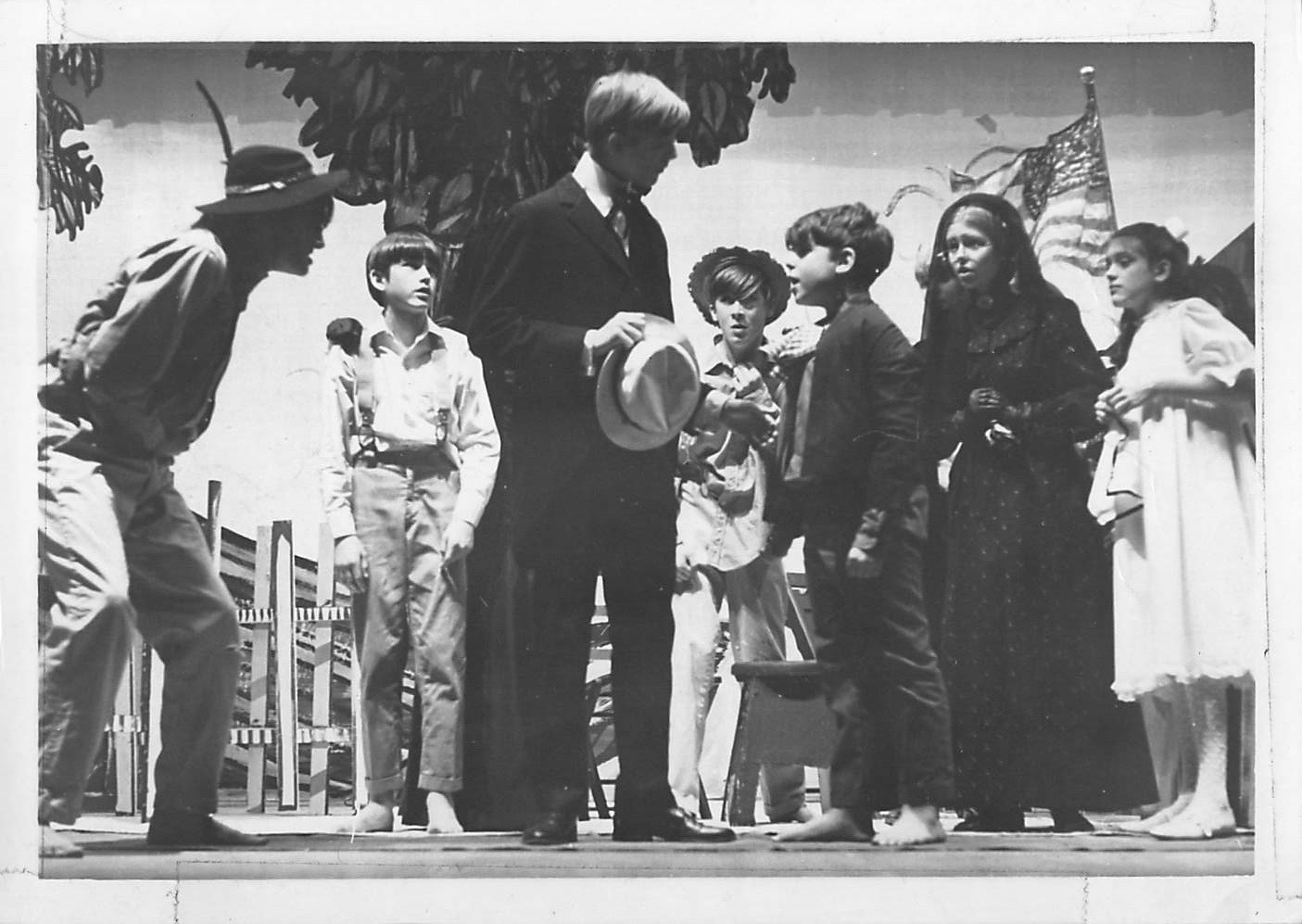

He remembers not being a good athlete during his teen years. In the housing project he lived in, boys in Murphy’s orbit played football, baseball and basketball. He felt left out — and he didn’t see that many options for other extracurriculars. For fun, he and a friend next door would imitate comics and tell jokes, which led to skits in their living room. After seeing a TV portrayal of Abraham Lincoln, they decided to create their own performances with homemade costumes.

Realizing they would need money to continue, Murphy got a can, labeled it “Children’s Theatre” and went around the housing project trying to raise funds for a nonexistent company. That proved to be a prophetic day, but not how Murphy expected.

“No one was going to give us money for this; they knew there was no children’s theater, and we were neighbors,” he says. “So we went to downtown Boston with the can and that worked.” He was caught by a cop, though, and forced to deal with his mother. Then, his welfare worker came up with an unorthodox idea. Sensing he might really be a performer, they placed Murphy in Boston Children’s Theater. Murphy was frightened at first, but the enrollment changed his life forever.

He writes in the book: “A life in crime led me to theater.”

With the bug for performing and staging productions, Murphy attended Boston University and started a theater company called the Boston University Stage Troupe, which still exists. After graduation, he began performing regularly and eventually became the Co-artistic Director of TheaterWorks in 1980. He stayed there for seven years.

While teaching at MIT and directing a production of Hamlet, Murphy met Robert Brustein, a playwright, author and founder of the Yale Repertory Theatre and the American Repertory Theater. Brustein recommended him for an open position at Emory University’s Theater Department. Although Murphy knew very little about the area, his daughter Ariel, to his surprise, suggested he take the job. He moved to Atlanta in 1989 and became the producing artistic director at Theater Emory.

During his tenure at the company, he staged approximately 19 shows and launched the Playwriting Center. Besides placing an emphasis on new work, one of his most significant accomplishments was helping to create an Elizabethan playhouse on campus. He also directed all over the city — including the Alliance Theater, Theatrical Outfit, Georgia Shakespeare Fest, Horizon, PushPush and the National Black Arts Fest — and throughout the world

Murphy eventually left the job in 2017. “I felt like [the position] needed younger or other voices,” he says. “I felt like I had carried it for a long time. I have this theory that every seven years, you go through a molting process, and you have to shed the skin you have. If you are an artistic director, the luggage gets heavier.”

After getting remarried, Murphy moved to New York and split his time between there and Berlin. He’s still active in theater, doing workshops and freelancing. In November 2024, he directed the Mel Konner Play Festival at 7 Stages Theatre in Atlanta.

Murphy’s daughter Ariel Fristoe is the artistic director of the acclaimed Atlanta company Out of Hand Theater. He did not expect her to go into theater.

More on ArtsATL: Luke Evans’ review of How to Make a Home, one of Out of Hand’s recent shows.

“I said to her: Don’t you think dentistry is interesting? I knew what [theater] cost, and I never tried to downplay that. I’d have seminars every year for Emory students. [I’d tell them], you live in a culture that is not going to be particularly supportive, [and you’ll] have multiple jobs if you want to survive. We tried to be practical around that. She came to live with me when she was in high school and flirted with theater. She fell in love with a group of interns who started their own theater company, and that generated something.”

Murphy has been proud watching Out of Hand take off. One of the pieces of advice he gave his daughter stands out: “Find people better than you if you want to learn something.”

“The demise of a lot of theaters is that people hire less,” he says. “Artistic directors hire directors so they don’t get shown up. Ariel was smart about that when she started Out of Hand. She was looking for people she knew would challenge her — and that’s why the company has gone on for 26 years with innovative ways of doing things.”

::

Jim Farmer is the recipient of the 2022 National Arts and Entertainment Journalism Award for Best Theatre Feature and a nominee for Online Journalist of the Year. A member of five national critics’ organizations, he covers theater and film for ArtsATL. A graduate of the University of Georgia, he has written about the arts for 30-plus years. Jim is the festival director of Out on Film, Atlanta’s LGBTQ film festival, and lives in Avondale Estates with his husband Craig.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.