Review: New exhibits at Spelman, Johnson Lowe and the Carlos

The end of winter and onset of spring means the city has come alive. After a relative lull over the winter, exhibition programming has returned in earnest to the city. Reflections on the aging and fading of one season into the next could, it turns out, also be used to describe three exhibitions that have recently opened.

At the Michael C. Carlos Museum, academia meets whimsy in Timothy Hull’s exhibition, titled Anonymous Fragments, which continues through June 29. Hanging in a gallery immediately off the Greek and Roman permanent collection gallery, fieldwork photographs from the creation of this exhibition are set in multiphoto frames, painted ceramic fragments under glass are flagged with potential attributions and diagrammatic paintings are hung around the walls.

But these are no 2,000-year-old artifacts of a long-dead civilization — these are new artworks created by Hull, sporting vibrant coloration and mottos such as “be gay do crime.” The artist is a lifelong resident of New York, and his process of humorously re-inventing ancient history has become the mainstay of his work, earning him media attention in the likes of Artforum and The New York Times.

The artworks in this exhibition were intended to be a conduit for a speculative view of ancient cultures, one which favors inclusion of sexual diversity, but they feel cheaply made — kitschy knockoffs of real artifacts. With so many possible imaginings of history, why not choose to envision gay people who lived in ancient cultures as adept craftspeople rather than caricatures?

At the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, black squares dominate the space — but this is no Russian Suprematism exhibition. Artists in this early 20th century abstract art movement isolated and explored the formal qualities of art — line, shape, color, value — the most notable of whom is Kazimir Malevich, who gained renown for a painting of a flat black square.

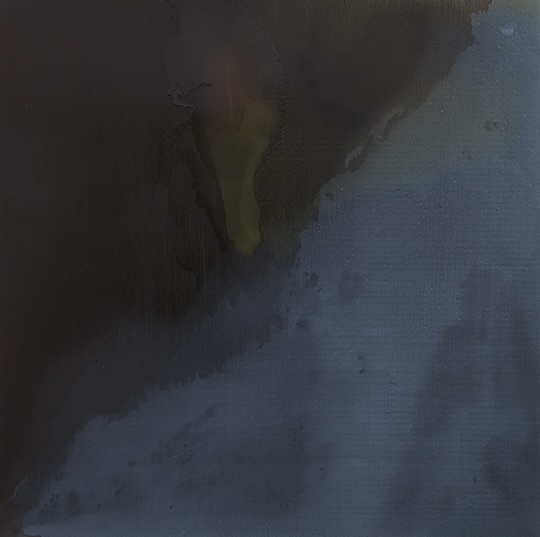

We Say What Black This Is, which continues until May 24, presents square paintings on canvas, panel and paper by Amanda Williams. Largely black, these compositions feature muted glimmers of color rising out of tenebrous grounds. According to the wall text, the artist is referencing “Blackout Tuesday,” a day of social media activism that transpired on June 2, 2020, in which participants posted a black square to their Instagram feeds to decry the racist killings of Black people at the hands of police in the United States. The paintings mimic Blackout Tuesday’s form and content to illustrate that the campaign, nearly five years on, is not forgotten.

Much like Russian Suprematist paintings, Williams’ artworks feel plain and flat. Relatively limited color and technical finesse gave me the impression they were largely one dimensional. But perhaps that is exactly the point. Although Blackout Tuesday, begun in the music industry, was conceived with high intentions in mind, as many Black activists have pointed out, its actualization was rather ineffective, falling short of instigating structural change and primarily serving as virtue signaling — a way of publicly showing that you or your organization are on “the right side of history.” So while Williams’ paintings do not have much depth, neither did the social media activism they reference. In this way, lack of depth is precisely what makes this exhibition most powerful.

Jimmy O’Neal’s solo exhibition, Spittin’ Image, which continues at the Johnson Lowe gallery through April 19, takes its name from the idiom “spitting image,” implying an exact likeness or replication of a thing. O’Neal uses this idiom to reference AI and other generative algorithms, which the artist has been using to create his artworks for almost 20 years. Feeding images of himself and text prompts into these algorithms, O’Neal creates sets of abstract imagery which are superimposed to create the visual structure of each artwork. These nearly unrecognizable meshes of the artist and computer-created images are painted with gray, white and colorless acrylics atop a mirrored panel.

At first glance, they read as flashy kitsch art. Studying them more carefully, I felt disgust at the references to bodily viscera and goopy paint — in one corner of an artwork floats an extracted eyeball, in the center of another a slimy looking fetus. Trailing around a third is a thin strand of colorless paint that is identical to a string of saliva.

This transformation from intrigue to disgust is a wonderful parallel to the initial wonder at the onset of a new technology and the ensuing horror when nefarious uses are discovered — for example, biometric logins for smart devices leading to facial tracking software surveilling nearly all public spaces.

New technologies are revelations — opening entirely new doors of possibility and providing avenues for making the impossible possible. With so much potential at our fingertips, it is easy to get carried away, but care is required. With unrestricted use of new technologies, we might just make a monster.

The incredible beauty of O’Neal’s exhibition derives from simultaneously showing both qualities of technology. These artworks flash in the light and catch your eye, but, get close enough, and you will see that some of them have literally caught an eye. Fortunately, visiting this exhibition won’t cost you an arm or a leg, and, for this, it is a must-see.

::

Leia Genis is a trans artist and writer currently based in Atlanta. Her writing has been published in Hyperallergic, Frieze, Burnaway, Art Papers and Number: Inc. magazine. Genis is a graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design and is also an avid cyclist with a competition history at the national level.

STAY UP TO DATE ON ALL THINGS ArtsATL

Subscribe to our free weekly e-newsletter.